Impressions of a European, artist and photographer, from the Strasbourg region, drawing teacher for a few weeks in Ban Na Teui, a village in southern Laos.

The Primary School - Ban Nateui

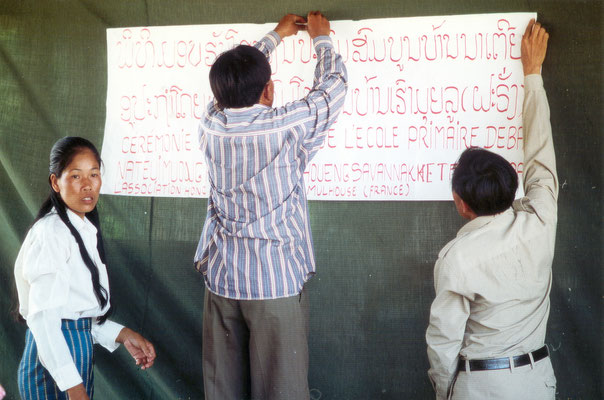

The project was initiated in 1994 by Franco-Laotians from the Mulhouse region (68) of the Hong Hienne Ban Hao / Alsace Laos association. It was made possible thanks to the support of the City of Mulhouse, numerous patrons, hundreds of donors and volunteers.

The villagers began work in 1999, the building was operational in April 2001, was inaugurated a first time at the same time as Pi Maï Lao (Lao New Year), then with the last finishing touches (ceilings, toilets, fence, gate) a second time in February 2004.

Origin of project

In 1994, Ban Na Teui Primary School was a wooden barracks with a sheet metal roof that had just been washed away by a hurricane. Three hundred children, coming from 15 km around, are crowded at 85 per class. During the monsoon season, dry places are rare...

First pickaxe shot

Bé then decided to rebuild it and took things in hand. With French and Laotian friends from the Mulhouse region, the challenge was met. A village architect voluntarily drew the plans for the new school and Bé, with the help of the village chief, formed 14 teams of villagers led by 3 site managers, all volunteers.

In 1999, the first pickaxe was struck. Tata Bé, with the funds collected in France, buys the materials and supervises the work with the site managers. The inhabitants of 3 villages will work as volunteers for 2 years to build the new school.

Inauguration

The building was inaugurated for the first time in April 2001 during a major celebration. The school was completed in February 2004 for the official inauguration, at the same time as the dispensary.

THANK YOU, volunteers, donors, patrons and friends of Laos, "our beautiful school...", as Tata Bé says, "... is the pride of an entire village".

The school in pictures

Second inauguration

A "falang" tells his experience

by Olivier LECLERC

Strange impression! As if by miracle, the whispers and rustle stop when I enter the classroom where about thirty toddlers from the village of Ban Na Teui are waiting for me. They have barely noticed me that they are all standing, greeting me in chorus, hands joined at face level, with an adorable "Sabaidee naikou" (hello Professor) that makes me shiver in my back.

I must admit that the stage of fright and anxiety are falling on me right now. I wonder if my presence in this school, lost between tropical forest and dry rice fields, as a teacher of improvised drawing can be useful to all these smiling kids who are watching me, their eyes devoured with curiosity. A "falang" (a Frenchman) who comes to have them drawn, what an event!

The reasons for my presence in this school, in the early hours of this bright January morning, require some explanation. In 1999, during a mountain bike raid between Vietnam Laos and Thailand with three Alsatian friends, we were captivated by Laos. Later, as time goes by to sort through the accumulated emotions, it is probably those felt in this small country that remained the most vivid in our hearts.

The distilled charm had bewitched us. All four of us fell in love with these Laotians who offered us abundant smiles, spontaneous kindness and a welcome that was inversely proportional to the poverty that, unfortunately, is the lot of the vast majority of the population. Laos, along with Cambodia and Myanmar, remains one of the poorest countries in the world, desperately lagging behind the development of South-East Asian nations.

Back in France, we met Bé Phouthavong, a French woman of Laotian origin living in Alsace. She had embarked on the difficult task of rebuilding the primary school in her home village to enrol 350 children. The old, long barrack, assembled with junk and junk, took water like an old skimmer and no longer withstood the devastating weather of the rainy season.

The new building, 64 m long, 7 classrooms plus two offices and a meeting room, was finished but there was no money for finishing, building toilets and fencing the land to prevent buffaloes, pigs, cows and animals of all kinds from coming to find refuge there and ruining the beautiful building.

In Laos, each village is in charge of building its own school, with the state simply paying teachers a poverty wage. Bé, despite his energy and enthusiasm, was running out of steam to organize parties to raise a few thousand euros. Unfortunately, the subsidies collected were far from the amount still needed to acquire the materials that would allow the villagers to finish the work of their school.

They had built it with their hands, were more than proud of it, and by this labor of convicts had appropriated it as much as their children. This action needed to be given a second wind. So Bernard Ponton and I decided to make a video film and a photo report for future awareness evenings. Thus, in April 2001 we arrived in Bane Na Teui for a crazy week of popular jubilation, the inauguration of the school being coupled with the Buddhist New Year celebrations.

To say that we were well received is far below reality! We were even sometimes embarrassed by so much concern from people who have so little. One hot afternoon I took refuge in the fragrant shadow of a flamboyant man to make some sketches, furtive reflections of the impressions of the festival. Seeing this, the teachers and the headmistress of the school asked me if I wanted to extend my stay to give drawing lessons to the children at the end of the holidays.

I was immediately seduced by this proposal, which unfortunately, due to lack of time, I could not honour. However, too attracted by this unusual idea, I promised them to come back for this purpose as soon as possible. And that's how, ten months later, I found myself, slightly dizzy by the adventure, in front of about thirty faces of smiling little Laotians up to my ears.

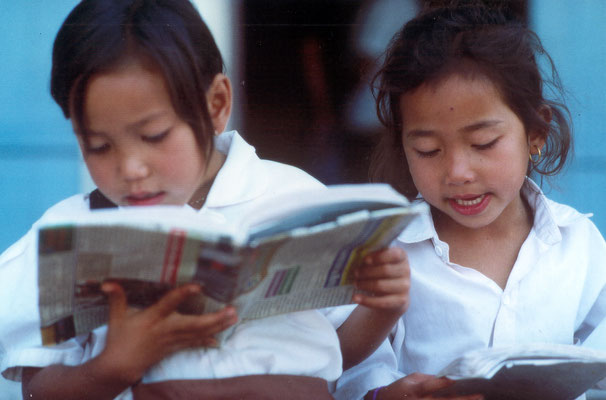

What strikes us immediately is the extreme destitution of the classrooms where, apart from an old blackboard with guingois against the wall, there are no teaching materials. The poor school supplies of the students consist of a notebook, a pen, a pencil stump, a ruler sometimes replaced by a piece of a hacksaw that is out of order and a textbook that falls apart.

We can only be heartbroken when we see these pathetic instruments at their disposal to educate themselves and hope for a better future for themselves and their country. And yet these people are lucky compared to their friends in many other villages! Since school is not compulsory, a multitude of children work from an early age to relieve their parents in agricultural and rice work or practice a thousand small resourceful jobs to survive.

It is better not to think too much about the injustice of the distribution of wealth in the world or risk falling into depression, or feeling fleetingly like an extremist soul. Let us begin the drawing session and at least try to bring a small stone to the fragile building of their future education. We distribute them sheets and coloured pencils, Bé translates some instructions and then we get to work together. I give the example of a large format view of a traditional Laotian habitat using pastel oil.

For their part, the children plunge on their leaves into a silence that disturbs me so much that at one point I turn around to check that they have not disappeared surreptitiously, leaving me alone on the board. No, I'm not! They're still here. Applied, focused as if they were taking an exam on which their lives would depend. From the youngest to the oldest, I will be impressed, intimidated too, by the seriousness that the students will give to this exercise, to which, for my part, I did not attach such importance.

The girls are always seated in the front rows, in front of the boys, while if there are young monks they are at the back of the class. This order has no exceptions and shows the decisive role of women in this society. Moreover, as adults, mothers of large families and tireless workers, they are the ones who, most of the time, will "wear the pants" in the household.

Men, certainly too used to being served by women, will on the contrary have an unfortunate tendency to let themselves live, preferring to put off until tomorrow, the next day is even better, what they could do in the moment. Always ready to do the "boun" (the celebration), they apply literally an art of living whose essential philosophy could be summed up in this maxim worthy of the Coué method: "Bo pen niang" in other words "everything is fine" or "there is no problem".

If this indolence, this cruel lack of initiative, this way of living from day to day, where stress has no place, are sometimes irritating, it is also partly for this reason that Laos and its inhabitants are so endearing.

Each class has its share of good surprises in store for me. Drawing is a universal art but, if one has not been provided by nature, or genetics, with this gift, no matter how hard one tries, the progress will always remain unrelated to the efforts made. This is immediately apparent. While some remain petrified in front of their leaves, which they observe like an impassable abyss, sketching waves of doodles, others immediately show surprising qualities.

Once the first moments of surprise and intimidation of seeing this kind of olibrius make them draw, they let themselves go to express the natural fantasy and spontaneity that are still the privileges of their age without constraints. There is no discrimination between girls and boys in this area. Both of them show the same artistic deficiencies or facilities.

I immediately notice the important role of nature in the lives of these children. They are still far from the constraints of their parents' lives and they are all kings of a still relatively unspoilt nature. Accustomed to frolicking without constraints, in the midst of vegetation and animals, many are capable of restoring their knowledge of the environment on paper.

Their sense of observation is unfailing when it comes to reproducing the shape of trees, their leaves or their fruits. Some of them make me discover surprising gifts of colourists. Of course, we would have to work longer with them to ensure that this is not just a coincidence, but if it were, it would be really promising.

After these two weeks of playing teacher, I think the experience was worth trying. It would even deserve to be renewed and extended. Yet, at the end of the last class, when all the children stand up and chant, hands together, "I greet the teacher and ask for permission to leave", once the joy of success is over, it is rather a feeling of unease that I feel about my such kind ephemeral students.

At the end of the primary cycle, once they have left their heavenly childhood to run and play in nature, to romp, free as the wind in the water holes and rivers, they will go to the village college which is composed of three classes built with the remains of boards and frames still usable from the old school. And then what?

Many could claim to succeed in higher education but, as in most cases, their parents will not be able to offer them, the hope of pursuing a brilliant education will be shattered. A good level of higher education is not necessarily a guarantee of social success. Bé's nephew, who did four years of geology after the equivalent of the baccalaureate, finds himself without work dragging his troubles for months in front of the television.

Once they leave the school system, they will struggle in search of jobs that they have few prospects of obtaining, since the almost non-existent industrial fabric does not allow them to absorb the flow of young people of working age. In Ban Na Teui the only employment opportunities are offered by the "salt mine" at the exit of the village. But when you see the dreadful working conditions of the ragged employees, who ruin their health under ruined buildings in a furnace temperature, you wonder if you should wish anyone to work here.

So, despite a proper education, their freedom of choice will be almost nil if the country's economic situation does not quickly take a giant leap forward. Back home, they will help them for a while in the arduous work of planting and harvesting rice and then, offended to live at their expense, taunted by the cruel feeling of feeling useless, they will go into exile to Thailand: Eldorado which opens their arms on the other side of the Mekong River.

Ah Thailand! The magical country that waters its deprived neighbour with glitter and rhinestones of inept TV soap operas and debilitating varieties that children, teenagers and adults devour with bright eyes of envy. A dazzling gallery of mirrors with larks that they will not resist for long.

I often shuddered as I watched all these innocent little girls draw, eager to know, so applied to their task, some with such promising talent. I couldn't help but think that within a few years we could, perhaps, find some of them, sold like cattle in the brothels of Bangkok. In writing this, there is no desire on my part to dramatize the situation, no exaggerated speculation. Unfortunately, we must be aware that the chances of such horror are high.

Now in Thailand it is increasingly difficult to find, even in the most remote places, young girls who are being deceived by promises of great jobs in the capital. The recruiters are now mainly recruiting in Laos and Cambodia, countries that are much less aware of the dangers of this type of proposal. With its 1500 inhabitants Bane Na Teuy is not very imposing, however, in recent years, some young girls from the village have had this terrible experience.

Everyone knows this, but it is the lot of family secrets too heavy to carry, for the sake of family members, we avoid discussing this subject, which leaves its shadow of despair and shame hanging over you in all circumstances. Thus, we learn that, since our last stay, some young girls, who had enchanted us with their beauty and the grace of their traditional dances, have flown, without warning, to Thailand. When Be tries to find out what they are doing there, no one can answer him precisely. We just hope these are serious jobs...

The boys are not to be outdone. They also risk prostitution, but it is mainly drugs that wreak havoc on their ranks. Bane Na Teuy also had the misfortune to see the devastating effects on a handful of his children who went to the Thai capital to seek their fortune. Those who escape these evil spells to find a normal job will be cut and chores to be done at will by unscrupulous employers.

Recently it has become easier for young people to obtain a work permit in Thailand but many are trying their luck without the precious sesame, thus becoming illegal workers. For those of you who are, the nightmare is not over yet. When, at the cost of multiple deprivations, they manage to amass a small nest egg and want to return home, they still have one last challenge to overcome.

As illegal immigrants, they must refranchise the border with the absolute obligation never to be controlled by the police. If, to make matters worse, this happens, the money they own is seized, they are thrown in jail and their families must pay a substantial fine to get them out of this mess. Of course, knowing the flow of "undocumented migrants" returning home, the Thai police, omnipresent on the border, are not depriving themselves of this opportunity.

Many unfortunate people fall into police traps, paying the price for an incredible system that takes back with one hand what it has sparsely given with the other to those it exploited yesterday. All these dark perspectives are running through my head. However, on closer inspection, the results are rather positive. Despite the language barrier, the children put their hearts into the work, many of them making superb drawings, and I think they were happy to see that people were interested in them, that they were not totally abandoned by the rest of the world.

The sabaï dii, the bright smiles that parents and children used to give me, when I walked through the streets of the village's broken laterite, the impression of being part of this small community from now on, will remain my greatest rewards. However, despite all my goodwill, I have the feeling that his two weeks may have as much effect on these laughing and mischievous kids as if I had thrown a rock into the Mekong River at the height of its flood. However, it was necessary to do so, hoping that the sum of such small actions would one day bear fruit.

I know that my judgment is unfair, overly pessimistic, but I can't get rid of the strange feeling of having been the sprinkler in history. While I had come to bring the help I could provide with my means, I now wonder if, against all logic, I was not the one who received the most throughout this wonderful adventure. I am really moved by it, but it was not the goal to achieve. I'll really have to try to do better next time.

Olivier LECLERC